The Apothecary’s Apprentice in Eighteenth Century England

Originally published at History Undressed

An Apothecary shop frequented by polite clientele (detail from The Apothocary circa 1752 by Pietro Longhi (1701–1785).

A nanosecond of background

I n England, as early as the 12th century, apothecaries (pharmacist physicians) belonged to the Worshipful Company of Grocers. This guild included the Pepperers and the Spicers and apothecary shops sold everything from confectionery, perfumes, spices, spiced wines, to herbs and drugs that were compounded and dispensed on the premises to the public. By the mid-16th century apothecaries were equivalent to today's compounding chemists, preparing and selling substances for medicinal purposes.

Yet, lack of regulation of this early pharmaceutical industry and the ease in which fraudulent apothecary-physicians known as “quacks” could advertise and dispense “remedies” meant that apothecaries were never given the respect they so desired as learned medical men.

Thomas Rowlandson’s illustration aptly entitled ‘Death and the Apothecary’ or ‘The Quack Doctor’ (note flying fish!)

Sir Samuel Garth’s satirical look at the apothecary’s shop in The Dispensary reflects this entrenched negative attitude toward apothecaries at the beginning of the 18th Century:

Here, Mummies lay most reverently stale

And there, the Tortoise hung her Coat o' Mail

Not far from some huge Shark's devouring Head

The flying Fish their finny Pinions spread.

Aloft in Rows large Poppy Heads were strung,

And here, a scaly Alligator hung.

In this place, Drugs in musty Heaps decay'd,

In that, dry'd Bladders, and drawn Teeth were laid.

The House of Lords ruling of 1704

In 1704 the House of Lords ruled that apothecaries could both prescribe and dispense medicines. This was a landmark ruling because it gave legitimacy to the apothecary as physician and thus an apothecary could say he belonged to a profession as member of the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries, rather than still be considered a tradesman. It thus ratified the status of the apothecary as a member of the medical profession, something the barber-surgeons had vehemently opposed for hundreds of years, and thus apothecaries finally had the self-satisfaction of legitimacy, if not in the eyes of their fellow medical men—the surgeons—then in their own eyes. The ruling also allowed the apothecary of the 1700’s to evolve into the general medical practitioner of today.

The 18th Century—changing perceptions of the Apothecary

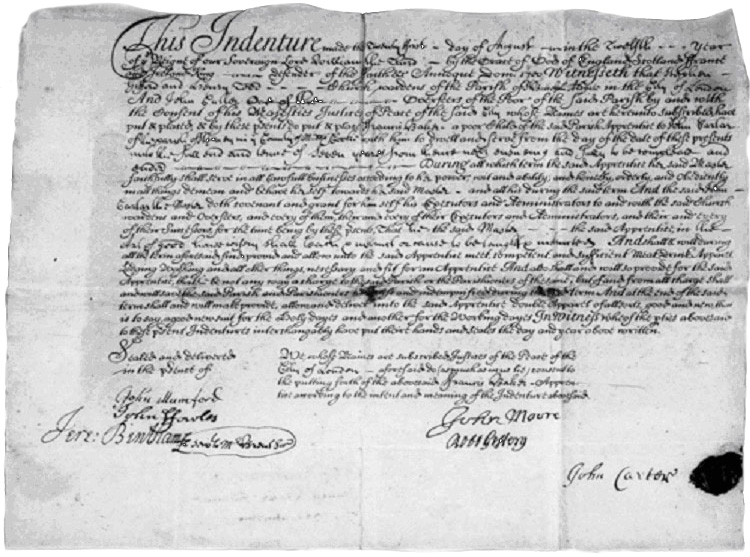

The landmark ruling of 1704 had given the apothecary legitimacy on paper, but it took a century—up until The Apothecaries’ Act of 1815, which granted apothecaries, amongst other rights, license to practice and regulate medicine, to slowly change the perceptions of the class-conscious Englishman as to the role and position of the apothecary in society. My Georgian Historical Mystery Deadly Engagement is set in 1760’s England, a time when medical reform and regulation of the Apothecary profession, especially with regard to education and training, was a major concern and continued to be for the rest of the 18th Century. Yet the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries made great strides in ensuring that the profession became professional, overseeing apprenticeships, registering master apothecaries and holding examinations for apprentices once their tenure with a master was completed.Apprenticeship Indenture document—courtesy London Lives 1690–1800 Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the Metropolis.

Boys as young as 12 were “bound” by way of an apprenticeship indenture to a master for seven years—the usual term to serve an apprenticeship for any trade or profession. An apprenticeship indenture was a legally binding document and money was paid to the master by a parent or guardian in exchange for the master agreeing to train the boy in their profession, and to supply the apprentice with food, clothing and lodging for the duration of the seven-year apprenticeship.

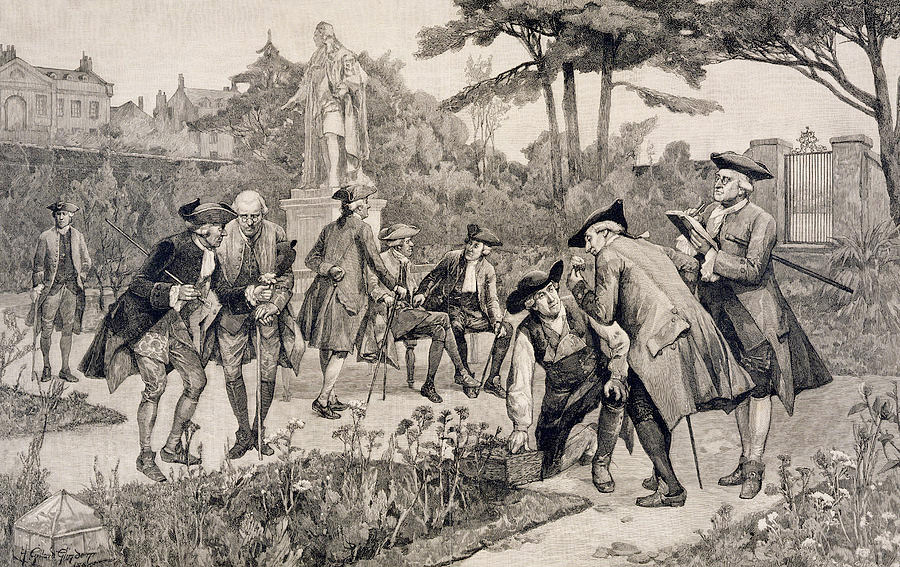

The Old Physic Garden of the Society of Apothecaries at Chelsea, 1750 (engraved by T.W. Lascelles)—the open-air laboratory for Master Apothecaries and their apprentices. The garden can be visited to this day.

During the seven-year apprenticeship a boy was taught to compound pharmacopoeia preparations, recognize drugs and their use and to dispense complicated prescriptions. Throughout the 18th Century, most medicines were derived from herbs, plants and vegetables and the Chelsea Physic Garden served as a place of instruction for the apothecary’s apprentice, providing simples and raw materials for the drugs manufactured in the laboratory of the Apothecaries’ Hall attached to the headquarters of the Company of Worshipful Apothecaries. An apprentice attended lectures and demonstrations in the hall of Barber-Surgeons and could participate in anatomical dissections if they wanted to. However, the Company of Worshipful Apothecaries did not require an apprentice to be examined on his expertise as a surgeon. So it was left entirely up to the apprentice to practice and become expert if he wished to use his skills as a surgeon—reason enough why barber-surgeons frowned on apothecaries who “crossed the line” and not only dispensed medicines and attended patients for general medical complaints but performed surgery—an extremely risky venture in the pre-anesthetic and unhygienic conditions of the 1700’s.

Masters usually took on one apprentice but there were instances of masters binding seven apprentices to his service. Given that parents paid a premium for their sons to be educated as apothecaries, these boys were less open to abuse. However, mistreatment at the hands of masters happened, and there are cases of boys being beaten, starved, worked almost death and made to live in appalling conditions. The usual place these apprentices lived out their seven years was at the back of the apothecary shop, in the workroom or “laboratory” with the herbs and powders, medicinals and apparatus needed for compounding. An unsafe and lonely place for a young boy if the master did not take the boy into his home and thus share his table and company of his friends and family.

In Deadly Engagement, we are introduced to Thomas Fisher—Tam—a footman in a noble household, who has five and half years training as an apothecary but is denied the opportunity to complete his apprenticeship when his master is disgraced and hanged for an offense he did not commit. It is as a footman that diplomat and amateur sleuth Alec Halsey first encounters Tam. It is a fortuitous meeting. Later, Tam is able to use his apothecary skills to save Alec’s life and finds himself temporarily employed as Alec’s valet. This is the start of a partnership and Tam is able to put his apothecary skills to good use in helping Alec solve a series of crimes committed at a country house engagement celebration.

Tam is luckier than most apprentices who fall on hard times and must take whatever work comes their way because Alec is determined that Tam will not remain his valet for long. He doesn’t want the boy to waste his talent as a healer and insists he complete his apprenticeship. What the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries has to say to Tam continuing on with his studies under the roof of a nobleman with the suspicion of murder over his own head is revealed in book two of the Alec Halsey mystery series, Deadly Affair.

References

Burnby, J.G.L. (1983) A Study of the English Apothecary from 1660 to 1760, Medical History, Supplement No. 3, 1983, The Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London

Porter, R. (1997) The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Aniquity to the Present, Harper Collins

London Lives 1690–1800 Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the Metropolis